Credit NASA, SDSS

A study using NASA's Swift satellite and the Chandra X-ray Observatory has found a second supersized black hole at the heart of an unusual nearby galaxy already known to be sporting one.

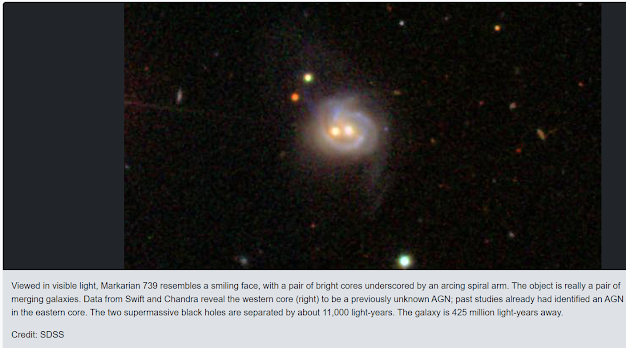

Viewed in visible light, Markarian 739 resembles a smiling face, with a pair of bright cores underscored by an arcing spiral arm. The object is really a pair of merging galaxies. Data from Swift and Chandra reveal the western core (right) to be a previously unknown AGN; past studies already had identified an AGN in the eastern core. The two supermassive black holes are separated by about 11,000 light-years. The galaxy is 425 million light-years away.

Credit: SDSS / NASA

_______________________________________________________________

Credit: NASA

The galaxy NGC 3115 is shown here in a composite image of data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT). Using the Chandra image, the flow of hot gas toward the supermassive black hole in the center of this galaxy has been imaged. This is the first time that clear evidence for such a flow has been observed in any black hole.

The Chandra data are shown in blue and the optical data from the VLT are colored gold. The point sources in the X-ray image are mostly binary stars containing gas that is being pulled from a star to a stellar-mass black hole or a neutron star. The inset features the central portion of the Chandra image, with the black hole located in the middle. No point source is seen at the position of the black hole, but instead a plateau of X-ray emission coming from both hot gas and the combined X-ray emission from unresolved binary stars is found.

To detect the black hole's effects, astronomers subtracted the X-ray signal from binary stars from that of the hot gas in the galaxy's center. Then, by studying the hot gas at different distances from the black hole, astronomers observed a critical threshold: where the motion of gas first becomes dominated by the supermassive black hole's gravity and falls inwards. The distance from the black hole where this occurs is known as the "Bondi radius."

As gas flows toward a black hole it becomes squeezed, making it hotter and brighter, a signature now confirmed by the X-ray observations. The researchers found the rise in gas temperature begins at about 700 light years from the black hole, giving the location of the Bondi radius. This suggests that the black hole in the center of NGC 3115 has a mass of about two billion times that of the Sun, supporting previous results from optical observations. This would make NGC 3115 the nearest billion-solar-mass black hole to Earth.

NGC 3115 is located about 32 million light years from Earth and is classified as a so-called lenticular galaxy because it contains a disk and a central bulge of stars, but without a detectable spiral pattern.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Alabama/K. Wong et al; Optical: ESO/VLT

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/chandra/multimedia/photo-H-11-248.html

____________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

The Chandra data are shown in blue and the optical data from the VLT are colored gold. The point sources in the X-ray image are mostly binary stars containing gas that is being pulled from a star to a stellar-mass black hole or a neutron star. The inset features the central portion of the Chandra image, with the black hole located in the middle. No point source is seen at the position of the black hole, but instead a plateau of X-ray emission coming from both hot gas and the combined X-ray emission from unresolved binary stars is found.

To detect the black hole's effects, astronomers subtracted the X-ray signal from binary stars from that of the hot gas in the galaxy's center. Then, by studying the hot gas at different distances from the black hole, astronomers observed a critical threshold: where the motion of gas first becomes dominated by the supermassive black hole's gravity and falls inwards. The distance from the black hole where this occurs is known as the "Bondi radius."

As gas flows toward a black hole it becomes squeezed, making it hotter and brighter, a signature now confirmed by the X-ray observations. The researchers found the rise in gas temperature begins at about 700 light years from the black hole, giving the location of the Bondi radius. This suggests that the black hole in the center of NGC 3115 has a mass of about two billion times that of the Sun, supporting previous results from optical observations. This would make NGC 3115 the nearest billion-solar-mass black hole to Earth.

NGC 3115 is located about 32 million light years from Earth and is classified as a so-called lenticular galaxy because it contains a disk and a central bulge of stars, but without a detectable spiral pattern.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Alabama/K. Wong et al; Optical: ESO/VLT

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/chandra/multimedia/photo-H-11-248.html

____________________________________________________________________________

Two teams of astronomers have discovered the largest and farthest reservoir of water ever detected in the universe. The water, equivalent to 140 trillion times all the water in the world's ocean, surrounds a huge, feeding black hole, called a quasar, more than 12 billion light-years away.

"The environment around this quasar is very unique in that it's producing this huge mass of water," said Matt Bradford, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "It's another demonstration that water is pervasive throughout the universe, even at the very earliest times." Bradford leads one of the teams that made the discovery. His team's research is partially funded by NASA and appears in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A quasar is powered by an enormous black hole that steadily consumes a surrounding disk of gas and dust. As it eats, the quasar spews out huge amounts of energy. Both groups of astronomers studied a particular quasar called APM 08279+5255, which harbors a black hole 20 billion times more massive than the sun and produces as much energy as a thousand trillion suns.

Astronomers expected water vapor to be present even in the early, distant universe, but had not detected it this far away before. There's water vapor in the Milky Way, although the total amount is 4,000 times less than in the quasar, because most of the Milky Way’s water is frozen in ice.

Water vapor is an important trace gas that reveals the nature of the quasar. In this particular quasar, the water vapor is distributed around the black hole in a gaseous region spanning hundreds of light-years in size (a light-year is about six trillion miles). Its presence indicates that the quasar is bathing the gas in X-rays and infrared radiation, and that the gas is unusually warm and dense by astronomical standards. Although the gas is at a chilly minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 53 degrees Celsius) and is 300 trillion times less dense than Earth's atmosphere, it's still five times hotter and 10 to 100 times denser than what's typical in galaxies like the Milky Way.

Measurements of the water vapor and of other molecules, such as carbon monoxide, suggest there is enough gas to feed the black hole until it grows to about six times its size. Whether this will happen is not clear, the astronomers say, since some of the gas may end up condensing into stars or might be ejected from the quasar.

Credit: NASA/CXC/PSU/G.Chartas